“If you ask me what my life will look like a few years from now, where I will be, what I will be doing–the honest answer is, I don’t know. But, I do know that I’ll still have football, I’ll have Arsenal, I’ll have a football family that just keeps growing, and we will all still have the shared currency of the beautiful game to connect us no matter what separates us. It’s the longest love story of my life and I couldn’t be more excited to see where it takes me next.”

I wrote these lines a few years ago concluding an essay for Unusual Efforts.

“You may come for the sport, but more often than not you stay for the people,” I also wrote.

Dave Seager is firmly in that camp. A Gooner friend that I’ve known for a decade, first online, then offline, who’s now like family.

A year on from the above essay, I wrote another for them that discussed the transformation of my relationship with the beautiful game and with the club that had adopted me as its own even before I realised it. Any long-term relationship will change and grow as the two participating entities do, like football allegiance and the love of the game. For the first time since becoming a Gooner, I was having to contend with that reality. A part of that is spells of feeling detached, of being disillusioned with where (especially the modern) game is headed, is already knee-deep in. We’ve all been there. The past two years more than any other. Many of us might still be there, others popping in and out as the fortunes of our clubs ebb and flow.

For Dave, his relationship with football and Arsenal irreversibly changed when he lost his son and Arsenal soulmate, Liam (yes, named after our famous Irishman) in an accident on New Year’s Day 2019. Everyone deals with grief in different ways. Dave eventually poured his into a new book project, dedicated to his boy.

“I hope this new book would have made you proud. The research and writing of it has proved some therapy and filled a small corner of the gaping hole you have left in my life, and in the lives of all who loved you.” (Author’s note, Arsenal for Everyone)

But it wasn’t just therapy and working, or rather writing, through his feelings that he wanted. It was a new perspective, a renewed manner of approaching the game he could no longer share with the one he most desired to.

“Suffering such personal trauma dramatically alters your perspective on life and places many things very firmly in context. Football, described by one of the comedians in the previous book as the most important of the unimportant things in life, is just that. I will always love the game and my Arsenal, but the club’s fortunes are now positioned in a new context. I still watch every match and relish each win, but the defeats and poor performances are no more than that. There is always the next match! So, to write an Arsenal related book, framed by my new perspective, had to be a meaningful project. It seemed appropriate to explore the football passions and the dramatic stories of individuals whose own support of the Gunners—and indeed whose lives—were also framed differently.” (Author’s note, Arsenal for Everyone)

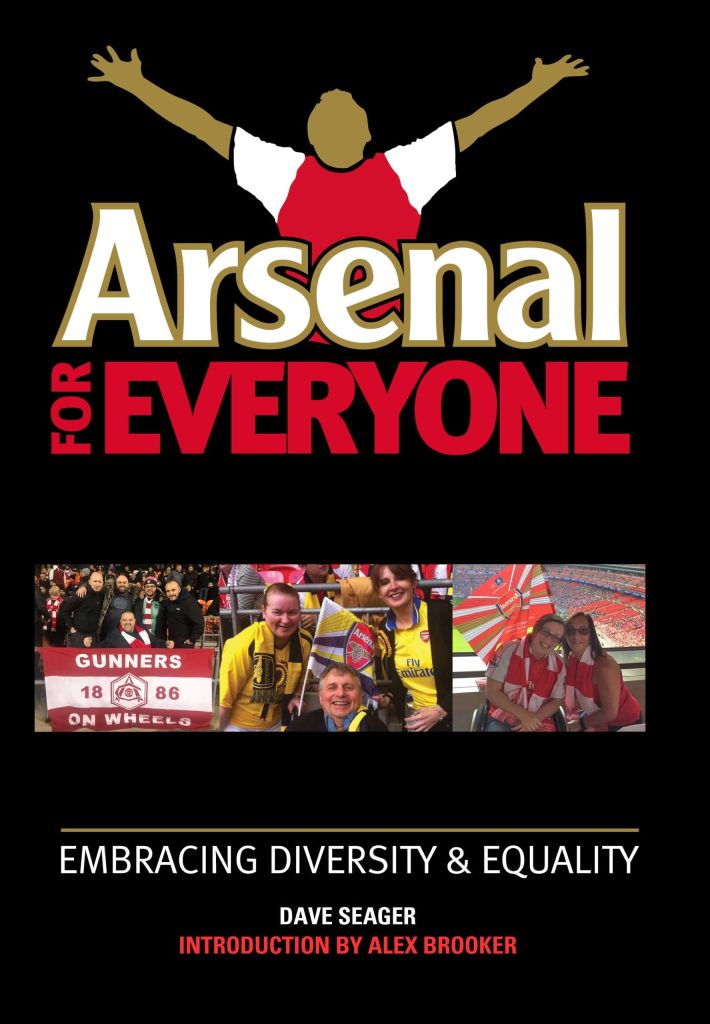

Arsenal for Everyone is a collection of chapters highlighting not only the fantastic inclusion work being done by the club from the start and the people involved in this ongoing process, but also the stories of fans who, through no fault of their own, had their support for the team framed differently, who, through various seemingly insurmountable challenges, still found their place in the Arsenal story, where their differently-abled bodies are left outside the stadium for the 90 odd minutes of each match and they’re just Gooners, communally connected, part of a shared history and landscape.

The book, supported and endorsed by Arsenal, opens with a piece by the co-founder of the Panathlon charity in England which has been providing sporting opportunities for children with disabilities and special needs for over 20 years, the same charity which will benefit from the purchase of this book. Ashley Iceton talks about the work they have been doing, their challenges and achievements, the changes they made when the pandemic hit and their support system had to move to a virtual platform; how, despite the 2012 Paralympics in London, there is still a lack of awareness and infrastructure at the grass roots and the work that needs to be done to further continue to level the playing field as it were.

—

Dave has a way of capturing the core essence of his subjects, with sensitivity, humour, and a simple narration that doesn’t interfere with the stories he’s telling and the people they are about.

Whether it is Thomas Clements who, as a kid with cerebral palsy, competed in the Panathlon events, was an excellent Team Captain, returned to coach after finishing school, and is now employed as a PE teacher; or Allan Marbet whose love for the club and the game has grown greater, the less he saw, who represented Great Britain internationally in athletics at the European and Olympic Games, who loves the anticipation, visualisation (via the special audio commentary and cues from his sighted partners), and imagination involved on match-day as a visually impaired supporter.

There’s ‘A Bergkamp Wonderland’s’ Danny Sweetman, a man whose voice is instantly familiar to those who have listened and listen to the podcast, but who, many may not know, suffers from spinal muscular atrophy and has had to deal with a lot to be a regular match-day-going Arsenal supporter. There’s Wayne Busbridge who was shadowed by sports documentary maker Ed Fenwick for ‘Over Land and Sea’ when he travelled to Baku for Arsenal’s ill-fated Europa League final with Chelsea and experienced first-hand the terrible conditions for disabled fans of both teams, who made sure to reach out to UEFA with his complaints through their authorised body CAFÉ (Centre for Access to Football)

In these pages you’ll be introduced to Jack Solomons, a 70-year-old Gooner with multiple sclerosis who’s had a challenging life even before his diagnosis but hasn’t allowed that to stop him from living his life and furthering his fandom; Craig Chamberlain, a deaf Gooner with various other disabilities, who found succour in tough times, as many of us do, in the wonderful online Arsenal community that rallied through his depression; a heartfelt letter from Julie-Ann Quinn to honour and celebrate the life of her Arsenal-mad son, Chris who passed away at 27 but wasn’t predicted to make it to his 16th birthday, and who gathered solace in the game and the team through multiple operations.

Take Redmond Kaye who talks about the confidence he built, despite cerebral palsy and severely limited hearing, after being taken to games by his dad, the coping skills learnt from being in a crowd, and how they’ve helped him be more independent outside of the stadium.

Take Brett Leverton who also talks about how being a football fan eased his journey from introvert to having more of a ‘social edge’, or the beautiful, inspiring story of Nicole Evans-Dear fighting through everything thrown at her, whose able-bodied husband said in his wedding speech, “We don’t need easy, just possible, and together we make everything possible”.

You might recognise Keryn Seal, who went from partially sighted to blind, from international cricketer to international footballer and captain (did you know that the Blind five-a-side game we know today originated in Spain in the 1920s or that West Brom are the only professional team with a Blind side?); and Jordan Jarrett-Bryan, an amputee with an amazing journey through able-bodied sport, disabled sport, professional sport, written journalism, and sports media and broadcasting.

We are also introduced to Mahlon Christensen from North California who represents the global character of the Gooner community. Mahlon became an Arsenal fan by accident after winning a shirt as a quiz prize in 2005, at a local pub, and seeing the cannon crest. Unable to fulfil his wish of serving in the forces like his grandfather had, because of his cerebral palsy, he’d gone to college to study military history, and he just knew that he needed to find out more about the club. Then there is the courageous Lyn Clarke living with the ticking clock of terminal illness and who, get this, comes from a Spurs family and turned staunch Gooner only after becoming disabled in her 50s!

All of these stories have in common the immediate sense of community that engulfs you as a fan, the escape it provides, the safe space it creates, the connections that it builds that go beyond those 90 minutes and the walls of the stadium. It even leads to a renewed sense of kinship with friends and family, as evidenced by Michael Watkinson, suffering from Usher’s Syndrome that has rendered him deaf with a progressive loss of vision, who points to the next step of inclusive assistance for the club – an interpreter who can assist deaf and visually impaired fans in following the on-pitch action using hands and a miniature replica pitch.

“It was Arsenal that automatically connected the relationship between me and my father”.

—

What Dave does really well in the book is connect the disability awareness and inclusion work done by the club (and what it still needs to do) to the stories of those actually impacted and affected by it; simultaneously showing us that we’re all Gooners first, everything else second, when it comes to our beloved club and the beautiful game, but also that a fandom is incomplete when part of the support isn’t fully, truly included.

In October 2013, Anthony Joy travelled for an away Premier League match to Selhurst Park, Arsenal playing the newly promoted Crystal Palace. He and other wheelchair-using Arsenal fans were positioned such that their view of the pitch was really poor to begin with, then non-existent once able-bodied fans directly in front of them stood and remained standing. Anthony, an active Twitter user, posted an angry tweet about it which caught the eye of the BBC who assigned a reporter to cover whether the PL and its clubs were failing their disabled supporters. An article was published that other outlets like the Guardian also picked up.

At Arsenal, ‘Arsenal for Everyone’ has already been an official club motto since 2008, but as we find out in the chapter dedicated to Alun Francis, the process started much earlier and he is a huge reason why. Alun, himself a wheelchair user because of his cerebral palsy, responded to an advertisement in the Guardian for a London Premier League club seeking to appoint a Disability Liaison Officer.

It was Arsenal who would become one of the earliest adopters of audio commentary for its visually impaired supporters, a system they have since streamlined, updated, and improved, with a highly trained team. This was while still at Highbury, with Alun was at the forefront of the developments. In fact, one of his first projects was to persuade the club to hire a tracked wheelchair, machinery that would lift a wheelchair and its owner into Highbury’s fabled art deco Marble Halls which had been denied to them because of accessibility issues until the final season at our still-spiritual home.

In comparison, the Emirates was built as an accessible stadium from the start, the club having consulted with a team including disabled supporters for their inputs during the planning stages. Under the capable guidance of Alun and his Disability Liaison team, the club has only expanded on these facilities and provisions. An example is one of the Premier League’s first Disabled Supporters Lounge where disabled fans who arrive early to avoid traffic and stadium crowds can wait, meet up with friends, enjoy refreshments and more, from upto two hours before kick-off to around 20 minutes before kick-off. In 2014, Arsenal were also the first PL club to provide an assistance dog toilet area in their stadium and the first to install a real changing places toilet.

In October 2019, Arsenal became the first PL club to partner with SignVideo to enhance the experience for their deaf and hard-of-hearing fans, like the aforementioned Redmond Kaye. Once the SignVideo app is downloaded, BSL supporters can now communicate directly with any department in the club, including the Disability Liaison Team, via a fully qualified BSL interpreter. Arsenal also offer Emirates Legend Tours or self-guided video tours for BSL fans.

Today, Alun is Disability Access Officer, Caroline Lemmon is the DLO, and Mark Brindle is the Supporter Liaison Officer, an approach Alun believes is only currently replicated at three other Premier League clubs, where the rest merge these three roles into two or even one.

“We want all visitors to Emirates Stadium to feel like they belong here and enjoy an equal matchday experience.” (Alun Francis)

In 2016, Anthony, Anne Hyde (current Chair and Secretary) and a few others were approached by Mark Brindle and Alun Francis at Arsenal about setting up the Arsenal Disabled Supporters’ Association. Anthony and Anne immediately realised the need to expand the committee members beyond those with visible disabilities like themselves.

“We needed input from each area to shape the conversation, for the fans to identify needs and then in turn bring those to the club.”

“Arsenal can drive me crazy, but they are a very progressive club when it comes to disability.”

—

Another fantastic development is Arsenal’s in-stadium ‘Sensory Room’ overlooking the Emirates pitch. It has been successful largely because of the prior collaboration between Alun Francis’ Disability Liaison Team and the Arsenal in the Community team and the latter’s ongoing outreach programmes. Sunderland Football Club’s facility, pioneered by Pete (then their Press Officer) and his wife Kate, came about from personal experiences with their three autistic children, who struggled with the overwhelming sensations of the match-day experience. The Shippeys’ idea was to create a safe space through a sensory viewing room for neurodivergent children which would allow them to still enjoy live games.

In 2014, Luke Howard permanently joined the Arsenal in the Community team as a Disability Officer, running Friday night football sessions for SEN (special education needs) and Autistic children at the Hub, among other things. Before that, he had volunteered with the club and worked on a zero-hours contract. He attended a conference where he heard the Shippeys speak. When he contacted Alun with this idea, he found out that the club was already in talks for such a room and he ended up being handed the reins to put it all together. Something he pulled off after consulting parents known from his work in the community, such as Gooner faithful Carly Wilde whose autistic son Reggie couldn’t otherwise go to games. It’s free, by invite, and rotational in order to accommodate as many new members as possible.

One of the team’s other successful ideas was ‘Sensory Hour’ at the Armoury which, previously, was a really daunting experience for neurodivergent children and their families. They launched it in collaboration with Adidas at the 2019 kit unveiling and until the pandemic, it was a very successful monthly feature.

“There is doing it, and there is doing it right, and our club does it right.” (Wayne Busbridge)

—

At the end of it, through the laughs and the tears and the human drudgery and inspiration seen within the pages of Arsenal for Everyone (and the near unanimous glowing words about the legend and gem that is Ian Wright, as well as Alun and his Disability Liaison Team), you realise that we, all of us in our different ways, use Arsenal as therapy, as an escape and narrative outside of real life with its own rules, emotions, and community. All while we remain suspended in this most beautiful of games.

“When I go to the Emirates, I’m not a disabled Arsenal fan, I’m just an Arsenal fan…It’s about falling in love with a football club and the journey that goes with it, just like for anyone else.” (Alex Brooker, introduction to Arsenal for Everyone)

As a fan, it was a reminder, a much-needed perspective about the privilege of being a supporter, any supporter, of this beautiful game; how much we can take it for granted. As an Arsenal fan increasingly disillusioned with the modern game and concerned about the running of the club on and off the pitch, it was also a timely reminder that, as Dave says in conclusion, “a football club, whoever owns it, is only as good as the people it employs, and boy do Arsenal have some wonderful and dedicated staff in their employ…despite the money in the modern game, and we cannot change where we are, a football club still has a duty to serve its community, local or further afield.”

An essential read for all Gooners, and, yes, all football fans invested in the game’s wider inclusivity.

You can order the book, signed by Dave, now for November delivery at Legends Publishing or you can wait for the official Arsenal launch at the Armoury on the 27th of November at the Newcastle match. (Look out for details.)